Sulfite

Sulfite (also known as SO2 or sulfur dioxide) is used in both wine and beer for its oxygen-scavenging ability and its anti-microbial effects. It can also be used for removing chlorine and chloramine from water or for no-rinse sanitizing.

Sulfite should not be confused with sulfate or sulfide.

Sources of Sulfite

Products

Sulfite is available in powdered form as sodium metabisulfite and potassium metabisulfite, and also in tablet form with the brand name Campden. These products are not entirely interchangeable, so it's important to note their differences when selecting a product. Neither potassium nor sodium affect the action of the sulfite, but they can have other effects.

- Sodium metabisulfite (Na2S2O5 also known as Na-meta or SMS) is 67% SO2 by weight. The sodium can affect flavor.

- Potassium metabisulfite (K2S2O5 also known as K-meta or KMS) is 58% SO2 by weight. The potassium is flavor neutral, so it is generally preferred in wine making. Potassium can also help some wines by precipitating with tartrate salts (see adjusting acidity in wine). However it may be less favorable in beer brewing because high levels of potassium are known to inhibit enzymes during the mash.

- Campden tablets come in different strengths and can be either sodium or potassium metabisulfite. If you use tablets, be aware of what form and strength they are.

- Sulfur discs or sticks can be burned to treat oak barrels.

Caution:

The powdered sulfite products give off SO2 gas that causes a choking sensation. Try to avoid inhaling the fumes.[1]

Proper Storage

Because sulfite reacts with oxygen, it needs to be stored in an air-tight container with as little air and moisture exposure as possible, otherwise it loses its potency. The shelf life is limited to 6-12 months even with careful storage. [2][3][4] The powder becoming clumpy is a sign of exposure to moisture.

Natural Sulfite

Sulfite is produced naturally by yeast during fermentation, and may be present at the end of fermentation in some amount, usually less than 30ppm although some strains can produce vastly higher amounts.[5][6] Yeast produce sulfite by reducing sulfate, although the concentration of sulfate may have only a minor effect on the amount of sulfite produced, depending on the yeast strain. Yeast also produce compounds during fermentation that bind to sulfite, decreasing the proportion of free SO2.

Sulfite Usage in Wine

Because of its utility, sulfite is an extremely common additive in commercial wines as well as homemade wine. It can be added at different points in the process to achieve different goals, most importantly the prevention of oxidation. Sulfite is practically a necessity for a wine that will be aged.

Legislation limits the total amount of sulfite that can be added to a commercial wine. This is not an issue for home brewers that avoid using rotten fruit; sulfite is safe to use in reasonable quantities and with proper management.[7]

Sulfite Before Fermentation in Wine

Sulfite can be used before fermentation to kill or inhibit the wild microbes naturally present on and inside the fruit or other ingredients like raw honey. To be clear, this is entirely optional. The wild microbes can be beneficial for wine in various ways,[8] so the winemaker should consider whether inhibiting them is needed.

If all the ingredients in the must are pasteurized, then sulfite is definitely not needed because there are no wild microbes present, assuming adequate sanitation is also used.

Sulfite for microbial inhibition is NOT one-size-fits-all. The amount needed depends greatly on the pH of the must. Using sulfite without measuring the pH may yield highly unpredictable results ranging from spoiled must to a fermentation that won't start.

Instructions

- The pH of the must should be measured. A pH meter calibrated right before use is the best tool for this; pH strips can be fairly inaccurate. Ideally we need precision within 0.1.

- If the pH is above 3.8, adjust it down to 3.8 with the acid of your choice.[9] See adjusting acidity in wine.

- Determine your target molecular SO2 level:

- For maximum microbial inhibition, targeting a molecular SO2 of 1ppm or higher is generally considered acceptable.[5][10]

- A lower amount (such as 0.5ppm molecular SO2) may be used to only partially inhibit the wild microbes, which may still allow some of their beneficial effects.

- Be aware that many wild microbes are resistant to sulfite and won't be killed by sulfite at reasonable concentrations. Heat pasteurization or possibly UV pasteurization are the only ways to guarantee that wild microbes are killed. However these processes may damage the flavor of the wine, unlike sulfite.

- Calculate the amount of free SO2 needed. To determine the amount of sulfite that needs to be added, use the sulfite calculator at FermCalc.

- Estimate the binding potential of the must. Adjust the amount of free SO2 to account for the binding. (How is best to do this?)

- Measure the sulfite with a scale if using a powdered form or count and crush the appropriate number of tablets.

- Gently dissolve the sulfite in water before adding it to the must. Briefly give it a gentle stir.

- The must should sit with the sulfite for approximately 24 hours. It should be left open to air during this time to allow some of the sulfite to gas off; cover with a towel or other method to prevent insects from getting in the must.

- Prior to pitching yeast, the must needs to be thoroughly aerated in order to neutralize the remaining sulfite so that it doesn't affect the pitched yeast, and to provide the yeast with oxygen.

Sulfite After Fermentation in Wine

Sulfite can be added after fermentation to protect the wine during aging both by preventing oxidation as well as inhibiting microbial activity. Be aware that adding sulfite during an active fermentation will likely not stop the fermentation and may have detrimental effects.

If Brettanomyces flavor development is desired, or if the wine will be naturally carbonated via bottle conditioning, then sulfite probably should not be used because it will inhibit the respective yeast and may lead to off-flavors. Fortunately, both Brettanomyces and the process of bottle conditioning are naturally helpful for preventing or reducing oxidation.

Sulfite should be added after the primary fermentation and any secondary fermentations (not to be confused with secondary vessels) are completed. Depending on how long the wine is aged and how it is handled, sulfite levels may need to be increased periodically. Measuring free SO2 is very helpful for making the determination as to when additional sulfite is needed and how much.

The level of free SO2 should generally be maintained in the 50-100ppm range during aging in order to prevent oxidation.[11] Molecular SO2 should be maintained above 0.6ppm to inhibit unwanted microbial activity. White wines (or any wine with low tannins) generally need higher levels of molecular SO2 to inhibit microbes. After the wine is packaged, the sulfite level will continue to decline.

The ultimate goal is to have the molecular SO2 level around 0.5-0.8ppm and free SO2 no higher than 100ppm at the time the wine is consumed. This may take some trial and error. Levels of molecular SO2 above 1.0 or free SO2 above 100 may cause faults. In particular, a high level of molecular SO2 causes a noxious choking sensation when inhaled. FermCalc is extremely helpful for calculating sulfite adjustments. If the wine pH is above 3.8, it should be adjusted downward with acid in order to increase the relative proportion of molecular SO2.

Instructions (for non-carbonated non-Brett wine)

- Wait for fermentation to complete in primary vessel, and you may allow it to clear for 1-2 additional weeks.

- Measure pH and optionally measure the sulfite level as well.

- Use FermCalc to calculate the amount of sulfite needed to reach the target free SO2 (50-100ppm free SO2 is likely needed). Molecular SO2 should be around 0.6-1.0ppm.

- Measure, dissolve, and add the sulfite to the secondary vessel when racking the wine.

- Repeat steps 2-4 whenever transferring the wine and when bottling.

Sulfite should always be used when stabilizing a wine by adding sorbate. This helps prevent off flavors from developing.

Sulfite Usage in Beer

In low oxygen brewing, sulfite is frequently used for its ability to actively scavenge oxygen and prevent oxidation.[12] Sulfite is not used in commercial wort production because the scale of commercial systems can much more efficiently limit oxygen exposure during the process. Its usage in home brewing is a "hack" to make up for the disadvantage of brewing on such a relatively small scale, with exponentially increased surface area relative to volume.

Outside of the context of low oxygen brewing, sulfite is rarely used in beer production (with the exception of #Chlorine Removal from Water).

Oxygen Scavenging in Beer

Low Oxygen Brewing

In low oxygen brewing, sulfite is added immediately before dough-in to help prevent oxidation during wort production (usually along with other oxygen-scavenging agents and process modifications). When beginning the transition to low oxygen brewing, the suggested starting amount of sulfite in the mash is 20-30ppm of sodium metabisulfite, which equates to 13-20ppm of free SO2. If sparging, sulfite should also be added to the sparge water before the sparge.

Because sulfite plays such an important role in preventing oxidation, SO2 testing should be utilized to track sulfite consumption. This information can be used to optimize the sulfite usage rate (which most brewers want to minimize). It is suggested to target a 5ppm level at the end of the hot side process (up until aeration or oxygenation), which provides a margin of safety without being excessive. Because sulfite acts as a surrogate marker for oxygen exposure, tracking when and how much of it is consumed can help identify procedural areas that need improvement with regard to oxygen exposure.

Instructions

- With the Free SO2 target in mind, the sulfite calculator at FermCalc can help calculate how much sulfite is needed, regardless of what product is being used. Alternately, if you have a particular sodium metabisulfite target in mind, you can use basic math to convert the ppm to grams (multiply the ppm by the number of liters and divide by 1000).

- Prior to use, weigh the sulfite powder or count and crush the tablets.

- Gently dissolve the sulfite in a small amount of water before adding it to the deoxygenated strike water (and sparge water if applicable). Avoid leaving it sit for an extended time.

- Residual sulfite at the end of the hot-side process needs to be fully neutralized (into sulfate) by using aeration or oxygenation a few minutes before pitching the yeast. Keep in mind that the wort will only increase in dissolved oxygen once all the residual sulfite is neutralized, so in order to provide adequate oxygen to the yeast, a higher amount of aeration or oxygenation will be needed compared to a process that does not use sulfite.

Sulfite at Packaging

Sulfite may be added when packaging to help delay oxidation during aging/storage. It can be used when not utilizing a low-oxygen process of wort production. Anecdotes suggest that this may even be used when bottle conditioning without any ill effects.[citation needed]

Microbial Effects in Beer

The pH of beer is typically too high for sulfite to have any anti-microbial effects, especially at the low amounts that are commonly used. In other words, sulfite does NOT inhibit yeast or bacteria in non-sour beer. (See #Chemistry and Mechanisms.)

On rare occasions, home brewers have used sulfite as a way to stabilize wild microbe flavor production in sour beer.[13] In this case, the low pH of sour beer enables the anti-microbial effects of free SO2.

In low oxygen brewing, residual sulfite at the time of pitching yeast (that hasn't been adequately neutralized by aeration or oxygenation) has frequently been reported to cause the production of hydrogen sulfide by the yeast. This is part of why it's important to neutralize all the sulfite a few minutes before pitching.

Chlorine Removal from Water

If tap water contains chlorine or chloramine (e.g. from a municipal water source), adding a small amount of sulfite is an easy way to remove it.[14] This is important because yeast may produce chlorophenols when in the presence of these chlorine compounds, which contribute an off-flavor commonly described as medicinal, plastic-like, or Band-Aid flavor, even in tiny amounts. Therefore the sulfite needs to be added at any point in time before aerating and pitching yeast, typically right after measuring the water.

Campden tablets are particularly convenient for removing chlorine or chloramine from tap water, where the dose needed is small and precision is unimportant.[15] Use as directed; normally 1 tablet treats 20 gallons of water. That equates to 0.022 grams of sodium metabisulfite per 1 US gallon.

Chemistry and Mechanisms

(In progress)

Dissolution

Metabisulfite salts dissolve in water and rapidly dissociate into ions.

| K2S2O5 + H2O | → | 2 K+ + 2 HSO3- |

|---|---|---|

| [metabisulfite salt] | [metal ions and bisulfite ions] |

Equilibrium

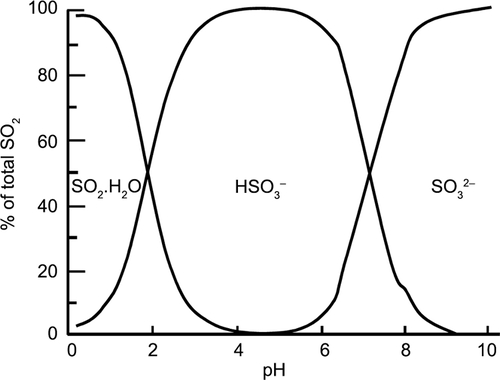

Three forms of SO2 exist in equilibruim once dissolved. Their ratio depends on pH.

| SO2•H2O | ↔ | H+ + HSO3- | ↔ | 2 H+ + SO3- |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [molecular SO2] | [hydrogen ion and bisulfite ion] | [hydrogen ions and sulfite ion] |

Binding

Some proportion of the sulfite binds to compounds in the wine or beer.

The binding fraction can be measured by adding sulfite, testing the free SO2, and testing the total SO2 (see SO2 testing). The difference between free SO2 and total SO2 will be the amount that is bound.

Oxidation Prevention

Bound sulfite protects compounds from oxidation.

Free sulfite reacts with oxygen.

Anti-microbial Activity

Molecular SO2 inhibits microbes.

Microbial Resistance

Coming soon!

Reactions with Halogens

Reaction with chlorine. Coming soon!

Sulfite Sensitivity

Should we beat this dead horse? Here are some articles:

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4017440/

- https://winefolly.com/tips/sulfites-in-wine/

- https://www.wired.com/2015/06/wine-sulfites-fine-heres-remove-anyway/

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/myths-about-sulfites-and-wine/

- https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fy731

Additional Resources

http://www.techniquesinhomewinemaking.com/home%20winemaking%20resources.html

http://www.brsquared.org/wine/Articles/SO2/SO2.htm

https://www.ajevonline.org/content/67/1/13

http://srjcstaff.santarosa.edu/~jhenderson/Sulfur%20Dioxide.pdf

Sulfite in beer http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0103-90162016000200189

References

- ↑ Sodium Metabisulfite MSDS Ineos.

- ↑ "Potassium metabisulfite." Pubchem.

- ↑ Kraus, Ed. "How To Tell If Your Potassium Metabisulfite Is Old." Wine Making Blog.

- ↑ "Technical Information Sheet: Potassium Metabisulphite - Preservatives." Murphy & Son, Ltd.

- ↑ a b Rotter, Ben. "Sulphur Dioxide." Improved Winemaking.

- ↑ Werner, M., Rauhut, D., Cottereau, P. "Yeasts and Natural Production of Sulphites." Internet Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2009 N12/3

- ↑ "Sulfites - USA." Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Food Allergy Research and Resource Program.

- ↑ https://www.mdpi.com/2311-5637/4/3/76/pdf

- ↑ Jolicoeur

- ↑ http://www.cider.org.uk/sulphite.html

- ↑ Pambianchi, Daniel. "A Review of Sulfite Management Protocols Based on SO2 Levels and Type of Wine." Techniques in Home Winemaking. 2014.

- ↑ Rabe, Bryan. LowOxygenBrewing.com

- ↑ https://www.themadfermentationist.com/2007/11/courage-russian-imperial-stout.html

- ↑ deLange, A.J. "Removing Chloramines From Water - Chloramines Removal." MoreBeer. 2013

- ↑ deLange, A.J. "Campden Tablets (Sulfites) and Brewing Water." HomeBrewTalk.com 2012